Fasting in black & white

“It’s your Jewish black fast again this week, isn’t it?”

“It’s your Jewish black fast again this week, isn’t it?”

This is the question put to me by a non-Jewish acquaintance.

“There is nothing black about Yom Kippur at all,” I tell him.

“If the day has any colour, it is white. Black signifies mourning, and Yom Kippur is not an occasion for mourning but for joy.”

“Joy?” he asks me. “Isn’t it too solemn for that?”

“Something can be solemn and happy at the same time,” I reply.

“There is definitely a joy and happiness about Yom Kippur – in fact even when we recite confessions of sins we use quite a bright melody; we actually sing at having our souls cleansed and the burden of sin lifted.”

“But you fast, don’t you? Surely that’s no fun?”

Answer: “Even the fasting, which is the best known Yom Kippur observance, is no morbid experience. What it does is to raise us above normal physical and material concerns; it gives the day a sense of spiritual exhilaration.

“People tend to wish each other Good Yom-Tov – ‘A Good Festival’, though the correct greeting is G’mar Tov – ‘A Good Sealing in God’s Books’, but Yom Kippur definitely is a festival”.

I tell my acquaintance that as well as fasting there are four other innuyim or restrictions – the prohibition of washing, anointing, wearing leather shoes and cohabitation.

“All these rules,” I add, “come from a verse in the Bible which tells us to afflict our souls (Lev. 23:32; Mishnah Yoma 8:1).

“There is a much loved Israeli rabbi, Shlomo Riskin, who thinks the Hebrew doesn’t necessarily denote self-affliction but is linked to the root anah, which means to answer or respond.

“To Rabbi Riskin the five innuyim respond to the recognition that something in our lives has gone wrong, and through them we begin to rebuild ourselves.”

“But no eating, no drinking, no sex? This helps to rebuild your lives?”

It’s clearly a good question. How do I answer?

“One element in the rebuilding comes,” I say, “when we note that each of the innuyim is an activity which is normally good, kosher and permitted.

“Eating and drinking are definitely permissible, of course they are, but on Yom Kippur we show who’s in charge. They don’t rule our lives; it’s we who master them.

“Sexual activity is permissible (Jews don’t have much regard for celibacy), but on Yom Kippur we can manage without it.

“A 3rd century rabbi, Rav, said in fact, ‘In the World to Come a person will be called to account for the legitimate pleasures which he denied himself’, and he might have added that one will also be called to account if we allow pleasure to make slaves of us.”

Conversation goes back to fasting, and I quote Abraham Joshua Heschel of Apt: “On Tishah B’Av with its tragic memories, who can eat; on Yom Kippur with its spiritual elevation, who needs to eat?”

I add, “What makes someone feel hungry on Yom Kippur is not that we are desperate for food, but the clock tells us it is our normal eating time, our body is used to its fix of food or coffee, and I am afraid there is often some rather distracting conversation in the synagogue pews about how well or badly a given person is fasting.”

This is what I tell my non-Jewish friend. To fellow Jews I have something to add, and I don’t really mind if he listens in. What I say is this:

If we gave Yom Kippur a chance, we would find that we can actually manage without physical comforts, pleasures and indulgences.

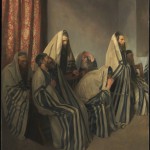

Yehudah HaLevi says in his Kuzari (3:5), “When they fast on this day they become like the angels. The fast is marked by humbling themselves, lowering their heads, standing, bending their knees and singing hymns of praise. Their physical powers abandon their natural functions, as if they had no animal nature”.

To be like an angel is possible one day in the year, though it is too much to expect it more regularly. Nonetheless, we ought at least to try to become more spiritual more often and to lose ourselves in the ecstasy of the Divine presence.

Fasting is also a symbol of compassion. We do without eating for a day once in a while, but there are many people who are hungry throughout the year, and our day without food should stimulate us to give practical support to those who have many days at a time without enough to eat or to give their families.

Yet, despite all this, there are those who watch the clock all day long. How slowly the hours pass for them! How uncomfortable they get as the day wears on! Others, made of sterner stuff, almost ostentatiously avert their gaze from the passing of time.

But both categories might not know that the pious men of the past did in fact watch the clock quite anxiously on Yom Kippur. Not in order to calculate how much of the ordeal still lay ahead, but to count how few precious moments remained to experience their spiritual closeness to God.