Satan Mekatrig

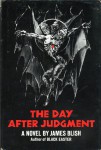

The Harry Potter books and films have fed an interest in a particular type of fantasy novel. The genre includes James Blish’s “The Day After Judgment”. It raises a modern theme, “Is God Dead?”

The Harry Potter books and films have fed an interest in a particular type of fantasy novel. The genre includes James Blish’s “The Day After Judgment”. It raises a modern theme, “Is God Dead?”

The debate involves Satan Mekatrig, “Lord of Hell, Great Enemy, Prince of Darkness”, who says that if God is no longer there, Satan would do a better job.

The name Satan Mekatrig is of course originally Hebrew and recalls rabbinic passages in which Satan, the devil’s advocate, is indeed mekatreg, man’s accuser.

Mekatreg – with the meaning of public prosecutor – has hebraised the Greek kategorein. The word figures in the poem Salachti on Kol Nidrei night, when the accuser, the kategor, is silenced so as to let the defender, the sanegor, speak his piece.

The notion of Satan bringing charges against human beings is found in Jastrow’s Dictionary of rabbinic words and developed in Israel Zangwill’s story, “Satan Mekatrig”, published in 1888, four years before the author’s famous “Children of the Ghetto”.

Joshua Trachtenberg’s “Jewish Magic and Superstition” traces the folkloristic fear of Satan and the means used in order to stop Satan in his tracks – amulets, Bible verses, Torah study, etc.

A weapon employed against Satan is the blowing of the shofar, and indeed there is a series of verses before teki’at shofar the initials of which form the words, K’ra Satan – “Destroy Satan”.

Not that Judaism was universally fearful of Satan. The rationalists regarded him as a mere symbol; only the folklore tradition took him seriously. The Bible has no independent being with the name Satan, not even in the Book of Job (ch. 1) where “Satan” accuses man before the Divine Judge. Satan is not a real person or an evil angel but an adversarial personification, a poetical expression for the evil fate that some people bring upon themselves.

Not everyone took the K’ra Satan idea literally, even though Rabbi Yitzchak (RH 16b) warned us l’arbev hasatan, to confuse Satan. Rashi says that Israel and its satanic enemies are engaged in a tussle. The Tosafot add that when Satan hears the shofar, he fears for his own future. Since the story of Bil’am (Num. 22:22) uses l’satan as a word for “to oppose”, it could indicate any form of opponent.

There was a time in ancient history when enemies (the Romans?) were alarmed when the Jews blew the shofar and they misconstrued it as a call to arms (RH 32b). The shofar-blowing was moved from its original early position in the Rosh HaShanah service in order to confuse the enemy and show them that this was a spiritual call to repentance, part of religious worship and not a military call to battle.