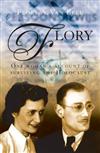

Flory – One woman’s account of surviving the Holocaust (book review)

FLORY: ONE WOMAN’S ACCOUNT OF SURVIVING THE HOLOCAUST

FLORY: ONE WOMAN’S ACCOUNT OF SURVIVING THE HOLOCAUST

Flory A Van Beek

An Hourglass imprint published by

Exisle Publishing, 2010.

Reviewed by Rabbi Dr Raymond Apple

Emeritus Rabbi of the Great Synagogue, Sydney

I read this book during Pesach (Passover). The book and the festival joined in a confluence of servitude and redemption. In the case of “Flory” the servitude was the Holocaust, especially as it affected the Netherlands. The redemption was Holland’s final liberation after the long and horrific years of the Nazi occupation.

Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik distinguishes between two types of servitude. To paraphrase his terminology, one category is political: a regime imposes an inferior status on the victim. The second category we can call psychological; it is one’s personality and dignity that are at stake.

Flory and her family certainly experienced the heavy hand of the first kind of servitude. It required all the resourcefulness that anyone could possibly muster. The risks were always excruciating. Sometimes the family were fortunate in being saved from danger. Flory often felt she could not go on and she reports that many Dutch Jews committed suicide. But on the whole the second type of servitude did not affect her, her husband and family. There were reserves of determination that somehow kept them alive.

At the beginning there was a feeling of confidence that Holland would never go under because of its queen. But there came a time when the queen had to flee. From then on, despite the queen’s morale broadcasts to her people, Holland was far from safe – certainly not for Jews (only 6000 of 140,000 Jews survived), but not for non-Jews either.

The remarkable thing about Flory’s experiences is the bravery and humanity of so many of the non-Jews who made survival possible for the few Jews they were able to shelter and help. One is reminded of Eliezer Berkovits’ comment in his “Faith After the Holocaust” that because of the brutality of the Nazis one cannot have faith in man – but because of the decency of at least some of the non-Jews one must have faith in man.

“Flory” raises the same searing question as every Holocaust memoir – how could a supposedly civilised people unleash such primitive savagery? The academics have exerted their minds and pens for many years on this question. Tragically, the answers are blowing in the wind.

What makes this book different is that throughout the years of suffering Flory kept cuttings, photographs and documents that were eventually buried in a tin box and later retrieved to enable the story to be told. The story had to be told. Flory knew she had to do it – but the task had to wait for thirty years until she felt able to write. The story she has written must be read. It is a remarkable tribute to the human spirit.