A House of Prayer for all peoples

The Bible is full of beautiful sentences. So much so that someone who came regularly to my Psalm study group once asked me, “Why are the Psalms so full of quotations?” He knew phrases like “the land of the living” and thought the Bible had borrowed them from general literature. It rather shocked him to be told that it was the other way around – that the world took for its own an amazing range of Biblical words, idioms and sentences.

The Bible is full of beautiful sentences. So much so that someone who came regularly to my Psalm study group once asked me, “Why are the Psalms so full of quotations?” He knew phrases like “the land of the living” and thought the Bible had borrowed them from general literature. It rather shocked him to be told that it was the other way around – that the world took for its own an amazing range of Biblical words, idioms and sentences.

They include the verse which is our subject of study this morning: Isaiah chapter 56 verse 7, Ki veti bet t’fillah yikkarei l’chol ha’ammim, “For My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples”. If we needed a Biblical motto of religious tolerance, it would be this (some find an echo in the Gospel phrase, “In my Father’s house are many mansions”: John 14:2, though that view needs further examination). The idea did not, however, originate with Isaiah. King Solomon included in the dedicatory prayers for the First Temple the words, “The stranger too, he who is not of Your people Israel… when he comes and prays towards this house, hear in Heaven Your dwelling-place and do according to what the stranger calls to You” (I Kings 8:41-43).

In order to understand the Isaiah verse we need to place it in context. What is the prophet saying? All who lead a pious and righteous life by means of justice, righteousness, Sabbath observance and refraining from evil will receive a Divine reward – not excluding the eunuchs and proselytes. All will be welcome on God’s holy mountain and be joyful in His house of prayer; their offerings will be accepted, for God’s house will be a house of prayer for all peoples.

The first question we have to ask is what is meant by “My house”. The house of God sometimes, especially in the Psalms, is a figurative expression for the Divine Presence (e.g. Psalms 23:6 and 27:4), but here in Isaiah we probably need a more literal interpretation since the verse twice refers to God’s “house of prayer”, suggesting a formal place of worship – though the concept of prayer without a sacrificial ritual seems theologically advanced.

On this literalist interpretation, the verse is concerned with the Temple in Jerusalem. All, even the gentiles, are welcome there provided they are pious and righteous and not idolaters. Herod’s Temple had a Court of the Gentiles – a large outer area where Jews and gentiles intermingled. However, there was a marble screen with a Greek and Latin inscription warning the gentiles not to enter the sanctuary itself. Jesus was aghast that commercial and other irreverent activities were taking place in this court (Matt. 21:12, Mark 11:15-16, John 2:14), and, quoting our verse, he declared, “Is it not written, ‘My House shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples’? But you have made it a den of thieves!” The Temple authorities were livid, but could do nothing to Jesus because of his popular support (Mark 11:17-19). We see that Jesus, for all his disapproval of what happened in at least part of the building, still regarded the Temple as important in the life of the people and endorsed Isaiah’s universalist vision.

Despite the literalist view, we can still interpret the house of God more broadly and see it as a metaphor for the world. In the Midrash God is a king whose palace, the world, gives Him delight (Gen. R. 9:4). A medieval philosopher says that the sky is the ceiling of the house, the earth its carpet and the stars its lamps (Bachya ibn Pakuda, “Chovot HaL’vavot” 1:6). Despite the tension in rabbinic thinking between nationalism and universalism – some liturgical passages such as Alenu incorporate both – no Jewish thinker denies that every human being is made in the Divine image and has a place in God’s house. (At this stage we are dealing only with this world and will consider the afterworld later.)

The Isaiah reference to a house of prayer does not preclude this interpretation, since there was no requirement that prayer be limited to the Temple and not elsewhere, even though sacrificial altars could not be erected at will. The Book of Proverbs advised, “In all your ways know Him” (Prov. 3:6), echoing the Shema with its dictate, “Love the Lord your God… these words shall be upon your heart; speak of them when you sit in your house, when you walk by the way, when you lie down and when you rise up” (Deut. 6:5,7). In a broad sense this is worship, making the whole world “a house of prayer”.

The idea that every human being, however unlikeable, has a place in God’s world is illustrated in the Midrash. An example is a story of a stranger denied a night’s hospitality, occasioning God’s retort, “If I can accept him in My world for seventy years, surely you can accept him for one night!”. A Chassidic echo is found in a saying of Rabbi Moshe Leib of Sassov, “What business has a drunken peasant in God’s world? But if God gets along with him, how can I reject him?” Homely anecdotes such as these bring Isaiah’s rhetoric into the categories of daily living. With a limitation. The verse became an expression of a highly tolerant attitude to the other, *provided they were not idolaters*.

The Decalogue rules out any form of idolatry. Passages against idol-worship come all through Tanach. Midrashic hyperbole says, “The law against idolatry outweighs all other commandments” (Mechilta to Ex. 12:6) and “Whoever rejects idolatry upholds the entire Torah” (Sifrei to Num. 15:22). God says that He and the idolaters cannot live in the same world. So why does He not destroy the idols? Answer: the idolaters often worship the sun, moon and stars, so should God destroy His Creation “because of fools”? (Mishnah A.Z. 4:7). Idolatry is not only foolish but is a false morality (I. Epstein, “The Faith of Judaism”, 1954, ch. 14) and idols are powerless to help human beings (Psalm 115). Rabbinic views of idolatry are presented in EE Urbach, “The Sages: Their Concepts and Beliefs”, 1987, vol.1, and CG Montefiore & H. Loewe, “A Rabbinic Anthology”, 1938). The Bible is not greatly interested in distinguishing between forms of idolatry, though the Mishnah Avodah Zarah was mostly concerned with the Greek and Roman pantheon.

The rabbis seem to have noticed a theological problem in our verse from Isaiah. Who are “the peoples” who may enter the house of God? Idolaters are ruled out. Proselytes are mentioned. But there are others, not yet adherents to the God of Israel, who are honest seekers, and the resident alien, the ger toshav, was a recognised category. Later, in post-Biblical times, semi-proselytes were a widespread phenomenon (Urbach, loc. cit.)

On the verse, “Therefore do the maidens love You” (Cant. 1:3), the Midrash says, “Even the nations of the world who recognise wisdom, understanding, knowledge and intelligence and attain to the substance of Your Torah, ‘love You’ with a perfect love” (Seder Eliyahu Rabbah 7).

The sages broadened the doctrine of tolerance by applying it to the afterlife, asserting that the tzaddikim, the righteous (the original text – in Tosefta Sanhedrin chapter 12 – may have read chassidim, “the pious”) of the nations of the world have a share in the World to Come. Though this is now normative Judaism, we should not presume that Isaiah was thinking of the afterlife when he said, ki k’rovah yeshu’ati lavo, “For My salvation is near to come” (verse 1), since yeshu’ah, “salvation”, is not an other-worldly concept in the prophets. In Tanach, “salvation” is in and of this world. The “life of the World to Come” is how rabbinic Judaism referred to life after death. Gentiles could be admitted to that life if they accepted the Seven Laws of the sons of Noah, which are basic ethical principles with one crucial theological element, the rejection of idolatry (Sanhedrin 56a).

Since Isaiah and the sages agree that entry to God’s house in any of its meanings depends not on theology (other than the rejection of idolatry) but upon deeds, we now need to ask questions about idolatry:

1. Does idolatry still exist?

2. Does Judaism regard monotheistic faiths as idolatrous?

By the time of the sages the subject was urgent and pragmatic. Could a Jew eat and trade with idolaters? The tractate titled Avodah Zarah, “Idolatry” (literally, “Strange Worship”) did not legislate against idolaters as such; it was addressed to the Jews, whom it aimed to prevent from coming into contact with and possibly being influenced by idolatry. Believing that idolatry had lost its force and that no-one really believed in it anymore (Urbach, p. 23), Rabbi Yochanan argued that “Their ancestors’ customs are in their hands” (Chullin 13b), which suggests that they did not consciously decide upon idolatry for and by themselves but merely acted out of force of habit. This made it easier for Jews to deal. We are not certain why Rabbi Yochanan limited his words to idolaters outside the Holy Land, and some authorities placed both Israel and the rest of the world on the same footing in this regard.

The growth of the daughter faiths of Christianity and Islam necessitated a further debate within Judaism if Jews were to be able to live and trade in Christian or Muslim lands. Christianity had derived from Judaism but its belief in Jesus was seen by Judaism as compromising the absolute Oneness of God. Did this constitute idolatry? Christian churches introduced religious icons. Were these to be deemed idolatrous? In answer to the second question Judaism remained critical but recognised that the icons were not objects of worship in themselves but artistic representations of Jesus and his family. However, the first question was more difficult.

The twelfth century giant, Moses Maimonides, averred at the end of his “Hil’chot M’lachim”, “The Laws of Kings (Government)” that Christians and Muslims, though in error, were dedicated to promoting the belief in the One God (“preparing the whole world to worship God with one accord”), and must be treated with respect (M’lachim 11:3-4). However, he also said, both in his Mishnah commentary (AZ chapter 1) and in his code (Laws of Idolatry 9:4), “The Nazarenes are idolaters”. The apparent contradiction is not easy to explain, though it is possible that the ruling that they are idolaters was constrained by his Talmudic sources whereas the more tolerant theological statement is his own view. Perhaps where he lived, in a Muslim environment, Jews were not under pressure to have commercial relations with Christians, and in any case he did not regard Muslims as idolaters (Letter to Obadiah the Proselyte). As we shall see, later authorities took a different view of Christians. Nonetheless, the passage in “Hilchot M’lachim” plays a highly important role in Jewish Heilsgeschichte and is strikingly advanced for its time.

A major stage in the debate on Christianity and Islam came in the thirteenth century, when Menachem Me’iri ruled that adherents of monotheistic faiths could not be deemed idolatrous as they upheld moral standards, respected the rule of law and were “defined by the teachings of religion” (“Bet HaB’chirah”, cited in “Shittah M’kubbetzet” to BK 38a, 113a). Me’iri’s ruling is discussed in Jacob Katz, “Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times”, 1961, especially chapter 10, significantly titled “Men of Enlightenment”. Later works had prefatory notes stating that references to idolaters did not apply to the peoples amongst whom the Jews lived (e.g. Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh De’ah, Romm edition, Vilna, 1895). This may have been a counsel of self-preservation, but it could be defended in its own right.

There is a line of development here. The attitude to the other is being refined all the time. In recent times it reached a further challenge. Granted that in the eyes of Judaism the other monotheistic faiths are, in Maimonides’ words, “in error”, is it able to regard them as “true religions”, or must it insist that the only true religion is Judaism itself? Whilst admitting that the others have their quality and their qualities, can it call them “true”? Are we to say with Esau, “Father, have you only one blessing?” (Gen. 27:38). Is there only one true faith, and if so what is the status of the others? Chief Rabbi She’ar-Yashuv Cohen of Haifa has said, “A nice garden is not just one flower but a variety… The world is God’s garden – it needs many flowers and we are God’s gardeners”. Beautiful words, but in ultimate philosophical terms are all the flowers of equal status?

Historically, the discussion has necessarily been restricted to the monotheistic faiths, to Christianity and Islam. Judaism has had little dialogue with eastern faiths. Its impression is that they either worship no god or at best elilim, “gods-that-are-no-gods”. It can recognise and appreciate their moral teachings but it is likely, when it has increased dialogue with them, to encompass them under the Biblical prohibition of idolatry.

I shall argue that the answer to the question of which if any is the “true” faith depends on three factors:

1. What do we mean by truth?

2. Whose task is it to find the answer?

3. In the long run, does it really matter?

Since it is the viewpoint of Judaism which we are seeking, we will be looking at Jewish material. Other faiths may have a different way of dealing with the problem.

Jewish theologians have long engaged with the question. There are universalists and nationalists – the one group arguing that Judaism is not necessarily the only true faith, the other that only Judaism is true. In between lies a position that posits that they all have parts of the truth but Judaism has most. The Maimonides school leads the first group, the chassidic Tanya school the second, the Judah HaLevi school the third.

A significant modern conspectus is provided by a theological symposium in “Commentary” magazine in the 1960s, reproduced in book form in “The Condition of Jewish Belief”, published by Macmillan in New York in 1966. Commentary sent five questions to 38 leading orthodox and non-orthodox rabbis and scholars, asking for written answers. Question 3 began, “Is Judaism the one true religion, or is it one of several true religions?” All agreed that God is the God of all mankind and that there is experience of the Divine outside Judaism. As a consequence almost all argued that there can be more than one true religion. Bernard Bamberger said, “I cannot believe that (God) has revealed Himself only to Israel”. Emil Fackenheim said that one God may relate Himself differently to different men or groups. Eliezer Berkovits said that Judaism is the one true religion – for the Jew. Immanuel Jakobovits said that Judaism is the only true religion but admitted that others make similar claims for their own religions.

However, several participants queried the methodology of the question. Arthur Hertzberg said that it implied what he called “a relativistic scale” with all faiths judged comparatively, and others agreed that though all faiths seem to share certain basic ideas and have a spiritual approach to life, each has its own mixture of elements – principles and practices, sacred events, pious paths and characteristic attitudes. David Greenberg says, “Each group selects a segment from the great arc”. How can the diverse segments be compared? What are we measuring?

“What is truth?” asked Pontius Pilate, and though I profoundly dislike mentioning Pilate, it is significant that Francis Bacon notes in his “Essays” that Pilate would not stay for an answer. In our case the answer may very well have to wait to be revealed by God at the end of days. Bacon also says that Pilate was jesting, but with us the question is highly serious. Solomon Schechter, a master of Judaic scholarship of an earlier generation, used to tell his students to leave a little to God. We cannot solve all the ultimate questions ourselves and it is arrogant to purport to do so. The Talmud has a concept known as teyku, “Let it stand”. In the messianic age the answers will become known. For Isaiah, that is when all the peoples will come “to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob”, and will heed and live by His word (Isaiah 2; cf. Micah 4).

Many Jewish texts assert that all the peoples will then adopt Judaism, though there are different views as to the form that Judaism will take. In Jewish thinking itself there are suggestions that certain commandments may fall away whilst others remain (e.g. Jerusalem Talmud, Meg. 1:5).

If we are to measure the Jewish doctrine of other faiths by the Commentary symposium, it appears that the universalist school is more or less normative amongst Jewish theologians, though many opt for the middle path that posits that all religions have part of the truth but Judaism has most. But we need to make two important qualifications to that statement. Both have to do with the reliability of the group whom Commentary dealt with.

The first qualification: current thinking in Jewish orthodoxy may prefer the particularist approach. This may be the conclusion that arises from a recent controversy involving Jonathan Sacks, the chief rabbi of Britain. His book, “The Dignity of Difference” (Continuum Publishers, 2002) stated that all religions have truth and God is higher than any one religion. He was severely taken to task by some fellow orthodox rabbis (who may possibly not have read the book but relied on media reports) who accused him of heresy. Sacks met with some of the critics and, while probably not resiling from his original view, agreed to re-write certain controversial passages. This was done for the second edition, which accorded ultimate truth to Judaism while not denying that there is wisdom in other religions. Which means that now we have two questions: not only “What is truth?” but “What is wisdom?”

The second qualification: what do the people think? Those who are aware of Isaiah probably pay lip service to his universalism. But the facts on the ground constitute a different picture. Jewish experience, culminating in the tragedies of the twentieth century, has reinforced chauvinistic tendencies. Statistics do not exist, nor would they help – but it is likely that most Jews would be particularistic and not want to know about other faiths and their spiritual quality.

So where does this leave us? The particularistic tendency, while it cannot be ruled out, may be an interim ethic. Long-term, the Jewish vision is universalistic. The world that Isaiah envisages is a messianic vision. The issue is how to work towards it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Classical Sources: Tanach, Mishnah, Gemara, Midrash, Maimonides, Shulchan Aruch

Epstein, Isidore, The Faith of Judaism: An Interpretation for Our Times, 1954

Jacobs, Louis, Principles of the Jewish Faith: An Analytical Study, 1964

Katz, Jacob, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times, 1961

Lauterbach, Jacob Z., Studies in Jewish Law, Custom and Folklore, 1970

Montefiore, Claude G. & Loewe, Herbert M., eds., A Rabbinic Anthology, 1938

Rabinovitch, Nahum L., “A Halachic View of the Non-Jew”, Tradition 8:3, 1966

Sacks, Jonathan, The Dignity of Difference, 2002

The Condition of Jewish Belief, 1966

Urbach, Ephraim E., The Sages: Their Concepts and Beliefs, 2 vols., 1987

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

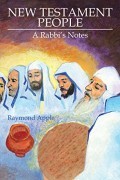

NEW TESTAMENT PEOPLE: A RABBI’S NOTES

NEW TESTAMENT PEOPLE: A RABBI’S NOTES

Rabbi Dr Raymond Apple’s book discusses some 98 themes in the New Testament and Christianity and shows how Jesus and the early Christians can only be understood against a Jewish background. Rabbi Apple never resiles from his own faith and commitment, but sees the book as a contribution to dialogue.

The softcover and ebook editions are available from Amazon, AuthorHouse, The Book Depository (free worldwide shipping), and elsewhere online.